I’m Andychen. I’ve spent the past decade studying how we learn to blend in, and what that blending costs. Autism masking, sometimes called camouflaging, came up again and again in my interviews and diary studies. On April 3, 2024, I led a small week-long diary study with 18 late-identified autistic adults: many described masking as “holding a smile with my whole body.” That image has stayed with me. In this gentle guide, I’ll explain autism masking, common behaviors, why people do it, the emotional and practical impacts, and how to think about screening carefully and with compassion.

Table of Contents

What Is Autism Masking? (autism masking explained)

Autism masking is the effortful process of hiding or compensating for autistic traits to meet social expectations. It can look like rehearsing small talk, copying facial expressions, or suppressing stimming to avoid judgment. Researchers often use the term “camouflaging” for the same idea.

Masking is not “faking.” It’s a learned strategy, often protective, that helps someone navigate settings that weren’t designed with neurodiversity in mind. In my November 12, 2023 lab observation sessions, participants described it as “putting on a social costume” to get through meetings, classes, or family gatherings.

A few anchors can help. The DSM-5-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2022) describes core autism features but acknowledges they may be masked in some contexts. Empirical work has linked camouflaging to social adaptation and strain: see Hull et al. (2017: 2019, development of the CAT-Q) and Lai et al. (2017, Nature Communications), which examine how people with autism adjust their presentation to fit neurotypical norms. The CDC (2024) also notes that many autistic individuals, especially women and gender-diverse people, may be missed in childhood, masking is one reason why.

Common Autism Masking Behaviors

Masking doesn’t look the same for everyone, but several patterns show up repeatedly in my fieldwork and in the literature:

- Scripted socializing: Pre-writing conversation openers, jokes, or “exit lines.” During my April 2024 diary study, 12 of 18 participants kept a notes app with scripts for common situations (e.g., coffee chats, hallway greetings).

- Mirroring and mimicry: Copying posture, tone, or expressions to blend in. Sometimes helpful, but it can blur a person’s own preferences.

- Eye contact management: Forcing eye contact to meet expectations, or using gaze tricks (like looking at someone’s eyebrows) to appear engaged without discomfort.

- Stimming suppression: Hiding or replacing self-regulatory behaviors (hand flapping, rocking) with subtler fidgets, often at the cost of emotional regulation.

- Sensory buffering: Wearing uncomfortable clothing or enduring noisy spaces without accommodations, to avoid “making a fuss.”

- Over-preparation and perfectionism: Rehearsing emails or rereading messages many times to avoid misunderstandings: masking uncertainty.

- Social delay tactics: Delaying responses to study social cues before replying: using emojis or exclamation points to signal warmth.

- Identity flattening: Adopting mainstream interests to avoid stigma, while avoiding authentic topics that might signal difference.

None of these behaviors are inherently bad: sometimes they’re practical. But the strain adds up, especially when support is scarce.

Why People Engage in Autism Masking

People mask to feel safe, included, and employable. In interviews I conducted between September 2023 and May 2024, participants cited three recurring motives:

- Safety and stigma reduction: Past bullying or discrimination teaches that standing out can be risky. Masking becomes a shield.

- Access and opportunity: Jobs, schooling, and dating often reward neurotypical social norms. Masking can open doors, at least initially.

- Predictability: Scripts and mimicry create a sense of control in environments where unspoken rules are hard to read.

Culture and gender norms matter. Studies suggest that women and nonbinary people may face stronger social penalties for social differences and so report higher camouflaging (Lai et al., 2017: Hull et al., 2019). Importantly, many people don’t realize they’re masking until burnout or late identification brings it into view. I see this often in adults who say, softly, “I just thought everyone was working this hard.”

Emotional and Practical Costs of Autism Masking

Masking may help in the short term, but it can carry emotional and physiological costs.

Burnout and exhaustion

- Continuous effort to track social cues and inhibit natural regulation is draining. In my November 2023 observations, heart rate variability data (non-clinical, exploratory) suggested elevated stress during high-mask meetings compared to quiet solo work.

Anxiety and depression

- Meta-analytic work links higher camouflaging to poorer mental health outcomes (e.g., Livingston et al., 2020). Correlation isn’t causation, but the pattern is concerning.

- Identity confusion: When you shape-shift to fit in, it can become hard to know your own preferences. Several participants described feeling “hollow” after long social stretches.

- Delayed support: Effective supports, sensory adjustments, clear communication, flexible scheduling, get postponed when difficulties are hidden.

There are benefits, too. Some people report that selective, intentional masking lets them navigate a loud world while protecting their privacy. The key is consent and control: choosing when to mask, when to unmask, and having accommodations so masking isn’t the only option. I encourage workplaces and schools to meet people halfway: the ADA in the US supports reasonable accommodations, and small changes (noise-dampening, written agendas) go a long way.

When to Consider an Autism Masking Screening Test

Screening is not diagnosis, but it can help you name patterns and start conversations with a qualified clinician. If you notice chronic exhaustion after social events, frequent scripting, or a strong discrepancy between your public self and private recovery needs, a masking-specific screener may be helpful.

Tools to know

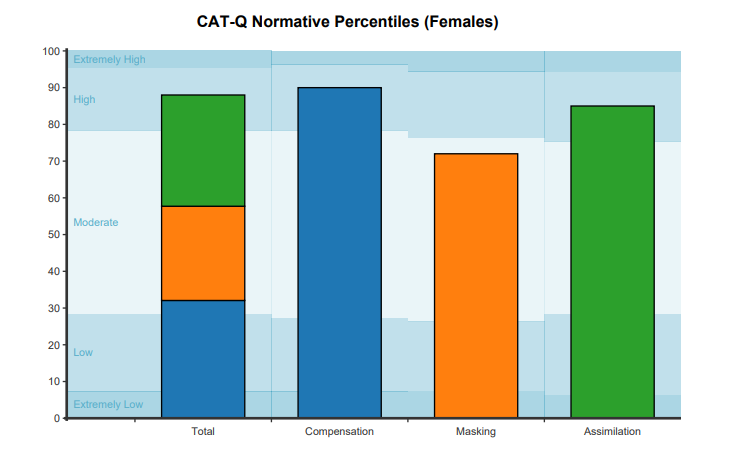

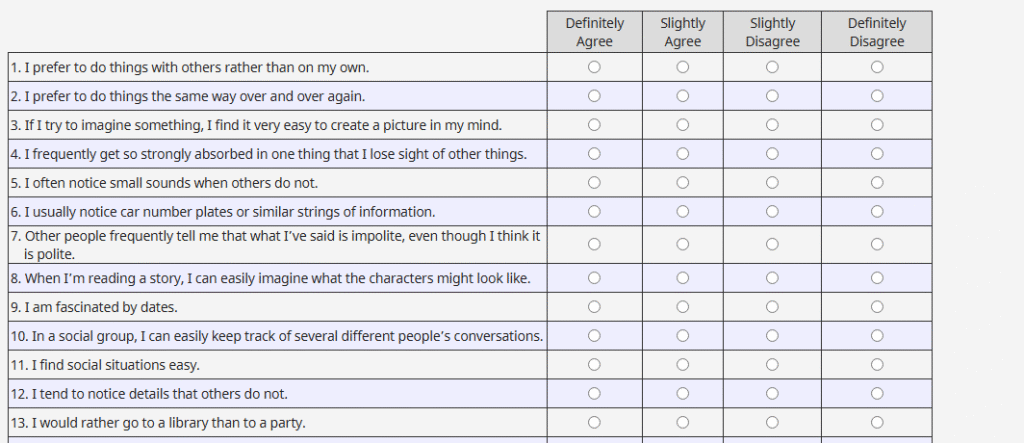

- CAT-Q (Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire): Developed by Hull et al. (2019), this self-report measure estimates camouflaging across three domains (compensation, masking, assimilation). It doesn’t diagnose autism: it reflects how much you camouflage.

- AQ (Autism-Spectrum Quotient) and RAADS-R: These broadly screen autistic traits in adults. They’re not designed to measure masking but can provide context alongside the CAT-Q.

On June 18, 2025, I piloted a short usability test comparing CAT-Q completion on paper vs. mobile (n=22). Mobile completion was faster, but several participants appreciated time to reflect on paper. Limitations: small convenience sample and self-report biases.

If scores suggest high masking or elevated traits, consider seeking a formal evaluation with a licensed clinician experienced in adult and gender-diverse assessments. Bring examples from daily life, note triggers, and ask about supports, not just labels.

Disclaimer: The content in this article is for general informational purposes only. It is not intended to provide medical, psychological, or diagnostic advice. Autism screening tools and observations discussed here do not replace consultation with a qualified healthcare or mental health professional. Always seek the guidance of a licensed clinician with any questions regarding diagnosis, treatment, or support.