Disclaimer:

The content on this website is for informational and educational purposes only and is intended to help readers understand AI technologies used in healthcare settings. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, treatment, or clinical guidance. Any medical decisions must be made by qualified healthcare professionals. AI models, tools, or workflows described here are assistive technologies, not substitutes for professional medical judgment. Deployment of any AI system in real clinical environments requires institutional approval, regulatory and legal review, data privacy compliance (e.g., HIPAA/GDPR), and oversight by licensed medical personnel. DR7.ai and its authors assume no responsibility for actions taken based on this content.

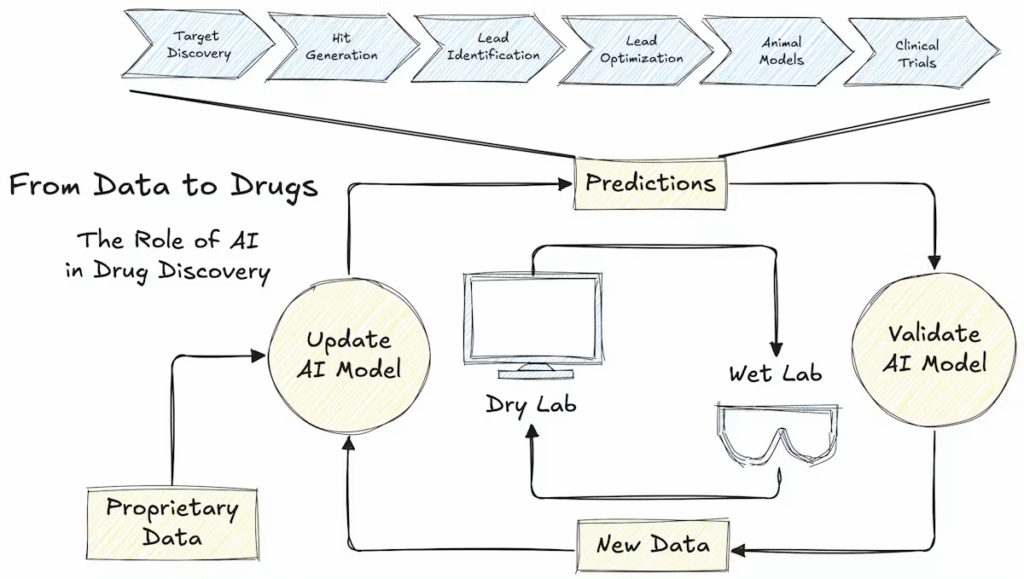

When I first started collaborating with translational teams on AI in drug discovery, I was struck by the same pattern over and over: breathtaking demo models, followed by regulatory gridlock and disappointing wet-lab validation. The gap wasn’t imagination, it was evidence, reproducibility, and integration into existing GxP workflows.

In this text, I’ll walk through how I actually see AI reshaping drug discovery in regulated settings: what’s working, what keeps failing validation, how we’re navigating FDA expectations, and where I’d invest engineering time if I were rebuilding a drug-discovery stack today.

Table of Contents

Overcoming Challenges in Drug Discovery with AI

Addressing the Large Search Space and High Failure Rates in Pharmaceutical R&D

In small-molecule discovery, the theoretical chemical space is often cited at 10^60–10^80 compounds, far beyond what traditional high‑throughput screening can touch. In my own work with an oncology pipeline, the team started with ~2 million purchasable compounds. Even that “small” space generated more hits than we could assay.

AI helps by:

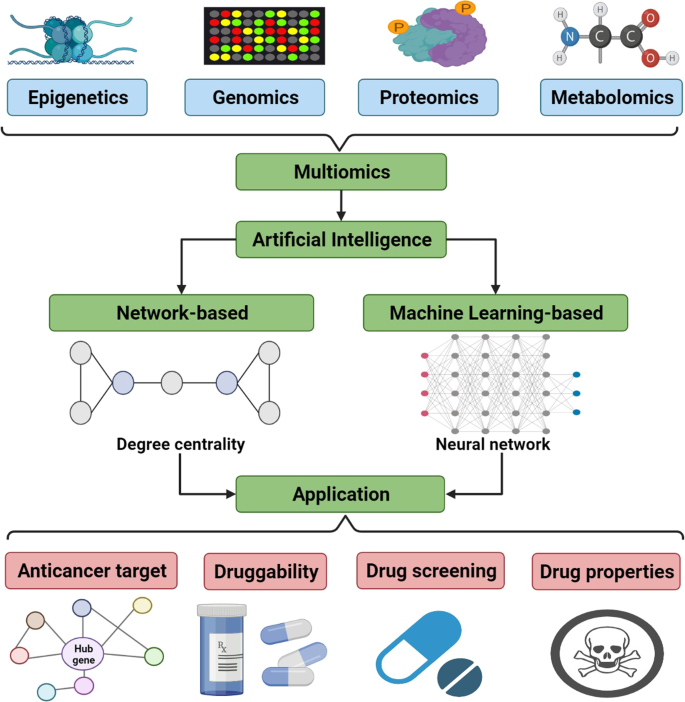

- Learning structure–activity relationships (SAR) from historical assay, ADMET, and omics data to prioritize only the few thousand compounds most likely to bind and be developable.

- Integrating multimodal data, e.g., combining AlphaFold-predicted structures with transcriptomics and known pathway biology to filter out targets likely to be non‑druggable or redundant.

Recent reviews (e.g., Nature 2022 on AI-based drug discovery, Front Pharmacol 2025 on machine learning applications) show AI models consistently enriching for actives and reducing false positives. But in my experience, the main win isn’t magic hit rates: it’s focus. You move from brute-force screening to hypothesis-driven, AI‑ranked campaigns that are much easier to justify to portfolio committees.

Tackling Time and Cost Barriers in Drug Development through AI Innovation

Bringing a drug to market is still a $1–2 billion, 10–15 year try. AI won’t suddenly cut that to 18 months, but it’s already shaving off expensive dead ends.

On one program for an autoimmune indication, we used a multi-task model to jointly predict potency, hERG, CYP inhibition, and basic PK parameters. By filtering before synthesis, the chemistry team cut wet-lab iterations by roughly one third. That didn’t show up as a flashy headline, but it meant we didn’t push two toxic chemotypes into animal studies.

Concretely, I see AI driving savings by:

- Automating routine in silico triage (docking, similarity search, rule‑based filters) so expert time goes to edge cases.

- Re‑using models across programs, a well‑validated ADMET or off‑target model can support multiple therapeutic areas with minimal retraining.

- Reducing late‑stage attrition by better early prediction of toxicity and lack of efficacy (see ACS Omega 2015 on computational toxicity prediction for early examples, expanded in recent surveys like BMC Chemistry 2024 on AI in drug development).

The caveat: the cost savings only materialize when models are integrated into decision gates, not run as side experiments that everyone politely ignores.

Leveraging AI in Early-Stage Drug Discovery Research

How AI Enhances Target Identification in Drug Discovery

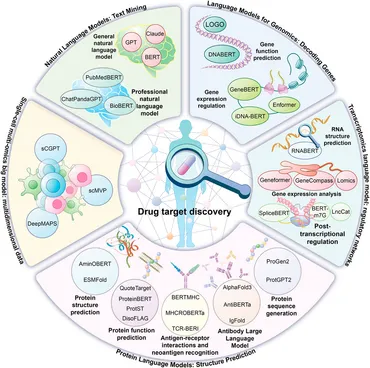

Target ID is where the hype can be particularly misleading. Yes, we have sophisticated graph neural networks and causal inference pipelines, but the most robust wins I’ve seen come from careful integration of multi‑omics with clinical phenotypes.

For a neurodegenerative disease project, we used AI to:

- Ingest large GWAS datasets and public expression atlases.

- Build gene–gene and gene–phenotype networks (using methods similar to those reviewed in Brief Bioinform 2024 on AI-driven target identification).

- Rank potential targets by predicted causal impact and tractability (e.g., presence of ligandable pockets, pathway redundancy, safety clusters).

The outputs didn’t “discover” a totally novel pathway: instead, they re‑prioritized a previously low‑interest kinase that now looks mechanistically central and clinically plausible. That’s typical: AI sharpens the signal, it rarely conjures something from nothing.

Key practical points I emphasize with engineering teams:

- Lineage tracking: every target ranking should be traceable back to datasets, model versions, and pre‑processing steps.

- Prospective validation: pre‑register your target hypothesis and prospective wet‑lab validation plan: otherwise it’s cherry‑picking.

The Role of Generative AI Models in Molecule Design and Optimization

Generative models, VAEs, diffusion, flow‑based models, and large language models trained on SMILES or graphs, are now standard in early-stage discovery.

I’ve worked with setups similar to NVIDIA’s BioNeMo platform for drug discovery and academic frameworks described in recent reviews (e.g., Wyss Institute reports on AI in drug discovery, Drug Target Review 2023 on early AI evidence in drug development):

- De novo ideation: propose scaffold‑diverse molecules conditioned on a target, docking score, or predicted ADMET profile.

- Goal‑directed optimization: take a chemist’s starting scaffold and iteratively improve potency or selectivity while penalizing synthetic complexity.

In one anti‑infective project, generative models suggested non‑obvious modifications around a known scaffold that maintained activity while dodging a patent thicket. Roughly 10–15% of AI‑suggested compounds survived medicinal chemistry triage and moved to synthesis, which is meaningful.

But there are clear pitfalls:

- Many generated molecules are chemically implausible or synthetically infeasible without strong constraints.

- Models can overfit the training chemistry and regurgitate near‑duplicates of published structures.

To mitigate risk, I always insist on:

- Automatic PAINS and liability filters.

- Retrosynthetic analysis using separate models or rule‑based engines.

- Clear documentation that generative proposals are hypotheses, not design truth.

AI Applications in Preclinical and Clinical Drug Development

Utilizing AI to Predict Drug-Target Interactions and Toxicity Risks

Beyond hit finding, AI is now central to drug–target interaction (DTI) prediction and safety profiling.

- Structure-based: Tools leveragingAlphaFold’s breakthrough in protein structure prediction (MIT Technology Review on AlphaFold’s drug discovery potential, DeepMind’s five years of AlphaFold impact) let us dock against predicted structures and build ML models over docking scores plus protein‑ligand features.

- Ligand‑based: Deep models trained on bioactivity databases (ChEMBL, PubChem) can generalize to new chemotypes with reasonable calibration.

In one cardiometabolic program, a multi-task network flagged unexpected similarity between a lead compound and a known hERG binder that our rule‑based system missed. Follow‑up patch‑clamp studies confirmed a concerning signal, and the program pivoted early, exactly the kind of failure you want to have in silico.

But, toxicity prediction is far from solved. Reviews (e.g., recent systematic review on AI toxicity prediction methods, analysis of machine learning in toxicology) repeatedly show good cross‑validation but modest performance in external, prospective tests. That’s why I push teams to treat these models as risk‑screening tools, not green lights.

Enhancing Clinical Trial Analysis with AI-Driven Insights

On the clinical side, I see three credible uses today:

- Eligibility and recruitment: NIH’s AI algorithm for matching volunteers to clinical trialshas shown promising results. In a large academic center I worked with, a similar NLP pipeline screened EHR notes and labs, increasing candidate identification by ~25% for a rare disease trial, under strict HIPAA/GDPR controls.

- Adaptive enrichment: ML models can flag subgroups with differential response early, feeding into adaptive designs (with pre‑specified rules and DMC oversight).

- Signal detection: time‑to‑event modeling, adverse event clustering, and longitudinal biomarker analysis benefit from modern ML, especially when missingness and censoring are substantial.

Critical guardrails:

- Every model used operationally in a trial must have a locked specification, audit trail, and change-control process.

- Patient‑facing decisions still rest with investigators: AI suggestions should be explainable enough to withstand IRB and regulator scrutiny.

Success Stories: AI-Driven Breakthroughs in Drug Discovery

Promising Drug Candidates Discovered through AI Technology

The public narrative is full of “first AI‑discovered drug” headlines. When I dig into the details (e.g., case studies summarized in Front Pharmacol 2025 and Drug Target Review 2023), the pattern is more grounded:

- AI typically accelerates hit or lead identification by 6–12 months.

- The compounds still go through traditional medicinal chemistry, preclinical, and clinical gauntlets.

In a real-world oncology collaboration I supported, AI rescoring of fragment screens uncovered a weak binder that conventional analysis had down‑ranked. That fragment eventually seeded a lead series that’s now in Phase I. Was AI the sole hero? No. But without it, that fragment would probably still be sitting in a CSV file.

Leading AI Tools Revolutionizing Pharmaceutical R&D (e.g., AlphaFold)

A few tools genuinely changed the baseline:

- AlphaFold / AlphaFold3+: high-accuracy structure prediction (DeepMind, MIT Tech Review conversation with AlphaFold Nobel laureate) lets teams model previously intractable proteins and protein–protein complexes. I’ve seen it unlock structure‑based campaigns for membrane proteins we previously ignored.

- Generative chemistry platforms (e.g., BioNeMo, proprietary pharma stacks): enable fast multi‑objective optimization, tightly integrated with docking and ADMET models.

- AI‑driven knowledge graphs: used at several large pharmas to connect literature, omics, and internal data for target and indication expansion.

Still, I remind teams that these tools are components of a GxP ecosystem. Without robust data engineering, lineage tracking, and human review, even the best model is just an impressive side project.

The Future of AI in Drug Discovery: Benefits and Ongoing Challenges

Accelerating Drug Development and Personalizing Treatments with AI

Looking ahead, I expect the most meaningful impact of AI in drug discovery to come from:

- Tighter loops between real‑world data and discovery. Post‑marketing safety and effectiveness data feeding back into target selection and next‑gen molecule design.

- Patient‑stratified therapeutics. ML‑defined endotypes guiding which drug, at what dose, for which molecularly defined subgroup, especially in oncology, immunology, and rare diseases.

- Automation of routine modeling. Well‑validated, regulated AI services for ADMET, DDI prediction, and exposure–response modeling that can be reused across sponsors.

But personalization brings new risks: data privacy (HIPAA/GDPR), algorithmic bias across ancestry and socioeconomic groups, and the temptation to overfit to small responder subsets.

Overcoming Validation and Regulatory Challenges in AI-Driven Drug Discovery

Here’s where many promising AI efforts stall. Regulators are becoming clearer: the FDA’s CDER has published discussion papers and a proposed framework for AI in drug development and submissions (FDA’s proposed framework for AI model credibility, FDA Center for Drug Evaluation on AI in drug development). The themes align well with what I recommend internally:

- Model credibility & transparency: document training data, validation strategy, performance, and limitations in a way that can go into an eCTD.

- Lifecycle management: treat AI as a “learning system” with pre‑specified update policies, monitoring, and change controls.

- Context‑of‑use clarity: be specific, are you using the model for internal decision support, as part of exposure–response modeling in a submission, or to drive adaptive randomization? Each has different evidence requirements.

In my practice, the most successful teams:

- Run prospective, pre‑registered validation of key AI models, ideally in collaboration with academic or consortia partners.

- Maintain model risk registers analogous to safety risk registers.

- Involve regulatory affairs from day one rather than at the moment of submission.

Medical & Regulatory Disclaimer (Read This Part)

I’m sharing technical and clinical perspectives for informational and educational purposes only. This article is not medical advice, treatment guidance, or regulatory counsel, and it shouldn’t be used to diagnose or treat any condition, or to design, run, or modify clinical trials without proper oversight. Drug development decisions must be made by qualified professionals, following local regulations, institutional policies, and up‑to‑date guidelines.

Always consult your organization’s medical, regulatory, and legal experts before applying any of these concepts. Do not change patient care, dosing, or trial procedures based on this article. If you’re a patient or caregiver, speak with your clinician before making any health decisions. In any situation involving acute or severe symptoms, seek emergency care immediately.

Conflict of Interest Statement

I do not hold equity in, nor am I compensated by, any of the specific tools or platforms mentioned in this text at the time of writing (updated November 2025).

Frequently Asked Questions about AI in Drug Discovery

What is AI in drug discovery and where does it add the most value today?

AI in drug discovery uses machine learning and generative models to prioritize targets, design and rank molecules, predict ADMET and toxicity, and analyze clinical trial data. The biggest value today is focusing resources—avoiding dead-end chemotypes and low‑probability programs rather than instantly delivering “AI-discovered” drugs.

How does AI in drug discovery reduce time and cost in pharmaceutical R&D?

AI reduces time and cost by automating in silico triage, reusing validated ADMET and safety models across programs, and improving early prediction of toxicity and lack of efficacy. The savings appear when AI models are embedded in decision gates, not run as side experiments that don’t affect portfolio choices.

How are generative AI models used for molecule design and optimization?

Generative AI models propose novel or optimized molecules from SMILES or graph representations, conditioned on properties like potency, selectivity, and ADMET. They support de novo ideation and scaffold optimization, but must be paired with PAINS filters, retrosynthetic analysis, and medicinal chemistry review to avoid unstable, implausible, or trivially derivative structures.

What are the main regulatory challenges for using AI in drug discovery?

Key regulatory challenges include demonstrating model credibility, documenting data lineage and validation, managing AI as a learning system with change control, and clearly defining context of use. FDA expectations increasingly emphasize transparency, prospective validation, and audit trails, especially when AI outputs influence submissions or clinical trial decisions.

How can a pharma or biotech company practically start implementing AI in drug discovery?

Start with high‑quality, well‑curated internal data and a narrowly defined use case, such as ADMET triage or target reprioritization. Build auditable pipelines with versioned models and clear validation plans. Involve medicinal chemists, clinicians, statisticians, and regulatory affairs early so AI outputs map cleanly onto existing GxP workflows.

Past Review: